Engaging with the United Nations as a Revolutionary

How African Nationalists petitioned to the UN during Decolonization

Belle Benavente

May 3, 2022

Getting to the UN

African revolutionaries often received funding from American or international organizations to travel to the UN. This included travel costs, accommodations, and support while petitioning at the UN. This photo shows Deputy President of the African National Congress, Oliver Tambo, holding Cora and Peter Weiss’s son. Tambo stayed at the Weiss’s home while petitioning the UN in 1963. Peter Weiss was the executive director of the Board of the American Committee on Africa. ACOA was particularly active in supporting Africans who were invited to petition the UN; often provided funds before and after trips, as well as organizing US tours for Africans.

Image of Oliver Tambo: https://africanactivist.msu.edu/record/210-849-33285/

Who got invited?

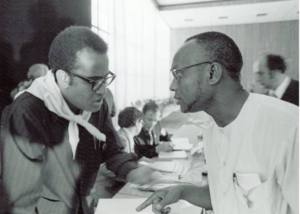

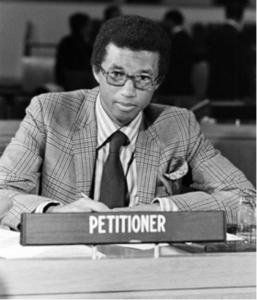

Revolutionaries traveled to the UN to convey updates about the situations in countries during decolonization. Those who petitioned and traveled depended more on their leadership within movements and resources than ideology. However, because of the Cold War, it was unlikely that those who identified as communists were able to travel to the US and petition. This is specific to petitioning the UN in New York, as delegations and meetings involving the UN had more diverse ideologies in Africa. This picture shows Mfanafuthi Johnstone Makatini, representative of the African National Congress (ANC), making a statement before the Special Committee Against Apartheid. This hearing marked the 15th anniversary of the establishment of the Committee (1978). Also shown is Elizabeth Sibeko of the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania (PAC).

Image: https://africanactivist.msu.edu/record/210-849-32284/

Opportunity

Petitioning to the UN allowed revolutionaries to establish networks and receive resources. Since organizations often sponsored petitioners, this allowed them to broaden their network of US-based resources and to network within the organizations. In addition, the UN often heard testimonies from numerous people, allowing petitioners to meet each other if they had not already; these petitioners were often from different parties, perspectives, and movements. This image shows the first democratically elected president of Togo, Sylvanus Olympio, with a delegation from the American Committee on Africa in Togo. ACOA had helped Olympio when he was a petitioner at the UN seeking independence and formed relations with him.

Image: https://africanactivist.msu.edu/record/210-849-31461/

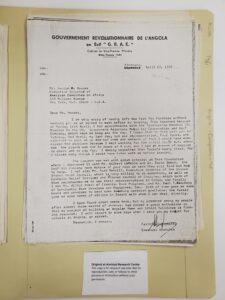

Image: 1967-11-13 Kounzika to Houser: speaking of opportunity in the US (African Letters Project database)

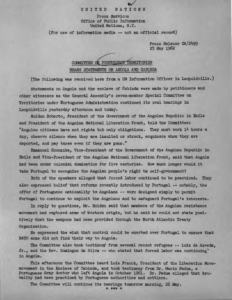

Special Committees

During decolonization, the United Nations created many committees to address country-specific situations. These were important for the recognition of liberation movements and tracking updates and progress in countries. There were committees such as The Special Committee on Portuguese territories; Special Committee of 24 on Decolonization; Special Committee against Apartheid; Committee to support the Republic of Guinea-Bissau; etc. This picture depicts Chairman Salim A. Salim of the Special Committee of 24 on Decolonization meeting with Amicar Cabral, Secretary-General of the Partido Africano Independencia da Guine e Cabo Verde (PAIGC). Established in 1961, the Special Committee 24, because of the number of members, reviewed the political, economic, and social situation in each of the remaining Non-Self Governing Territories on the UN list. The committee held meetings in several countries to discuss Southern Rhodesia, Namibia, and the African Territories under the Portuguese administration.

Image: Ihttps://africanactivist.msu.edu/record/210-849-31357/

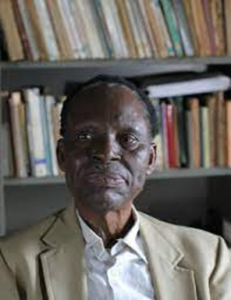

Emmanuel Kounzika

Image: https://www.tchiweka.org/pessoas/emmanuel-kunzika

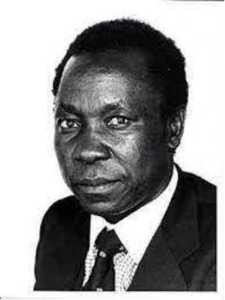

Emmanuel Kounzika petitioned the UN for the first time in 1962. Kounzika was the leader of the Democratic Party of Angola and then became Vice-Premier of the National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA) and Revolutionary Government of Angola in Exile (GRAE). He focused his efforts on Angolan refugees in the Congo and petitioned the Special Committee on Portuguese Territories. While he focused mainly on social services for refugees, he was an essential political representation for the Zombo people, with whom his political party identified. He spoke of the Portuguese administration’s continued use of forced labor, the longevity of the oppressive Portuguese colonial rule, and updates on the liberation movements involved. This United Nations document of the official record of this meeting states the overall points made and the revolutionaries that spoke, such as Kounzika, Holden Roberto, many refugees, etc.

Eddison Zvobgo in Prison

The story of a convicted patriot in Zimbabwe

Cole Golden

May 4, 2022

Eddison Zvobgo, like millions of his people, was a victim of European colonization in the province of Southern Rhodesia, today known as Zimbabwe. He decided to fight against the oppression through the formation of the National Democratic Party, a political group with the aim of removing the minority white rulers from power. Here, he worked under Joshua Nkomo and began his work to liberate his home. In 1961, he was sent by Nkomo to New York City to appeal to the UN on the NDP and ZANU’s behalf. When he returned, however, he was greeted by handcuffs as he was placed under arrest by government officials.

Zvobgo was sentenced to one year of imprisonment for his acts against the state, a ruling which he appealed in the Gwelo Magistrate’s Court. Unsurprisingly, he lost his case, and his sentence was upheld, being accused of attacking colonialism in Rhodesia and the current government. Though his sentence was set for twelve months, he would not be released for seven years, as unrest in Southern Rhodesia was soon to turn to violence.

Enough was enough for the people of Zimbabwe and the War of Liberation had begun. Small-scale attacks commenced against the Rhodesian government by both the Soviet-backed ZAPU party and the Chinese-backed ZANU party. This was a long and bloody war that would last for fifteen grueling years. Because of the outbreak of the war, the sentence of Zvobgo and the other arrested opposition leaders would be increased to an indefinite status. According to the Rhodesian government, this was under the justification that Zvobgo was “likely to commit acts of violence throughout Rhodesia”.

Zvobgo was first sentenced to time in Salisbury Prison. He spent a good amount of time there before the war broke out and his sentence was extended. Once this happened, he and many other resistance leaders were moved to Rhodesian restriction camps. Zvobgo himself was transported to Sikombela restriction camp alongside future president Robert Mugabe and other founding and leading ZANU officials. Sikombela was one of the largest Rhodesian restriction camps and was surrounded by miles and miles of dense jungle. For this reason, it was lightly guarded as no prisoner wanted to risk the trek through the dangerous jungles packed full of aggressive animals. There were no cells or no bars to hold prisoners, just cheaply made tin huts combined with scorching heat. The prisoners were given only the bare essentials for survival in the form of food and water. It was a horrible existence for Zvobgo, the rest of ZANU’s leadership, and every other mistreated person who was convicted to one of the many Rhodesian restriction camps in Zimbabwe. Today, the Sikombela restriction camp is preserved as a historical monument as a reminder for the people of Zimbabwe of what those before them paid for their freedom.

Despite the hardships that Zvobgo endured while in prison, he was not idle. He used his time in prison to get an education in law from the University of London, though this would not have been possible without George Houser. While in New York prior to his arrest, Zvobgo became linked with George Houser, a man who has aided many of Africa’s great leaders in their journeys to free their homes from their colonial oppressors. George Houser funded Zvobgo’s endeavor and thanks to him, Zvobgo was able to further his education and even pass the Rhodesian Bar Exam while imprisoned.

Zvobgo was released in 1971 and was immediately sentenced to exile. He traveled to Canada and then to the US to study Law at Harvard University. All the while, he was continuing his efforts to appeal to the UN on Zimbabwe’s behalf alongside figureheads such as Joshua Nkomo. Both Zvobgo and Nkomo insisted that war would continue for as long as the minority white rulers remained in control of Zimbabwe. All the while war was in fact devastating the region, and the patriot fighters showed no signs of quitting. Additionally, international sanctions began taking place as Rhodesia was condemned by many international powers.

Zvobgo at the UN: https://youtu.be/uaSPOh2uqQ0

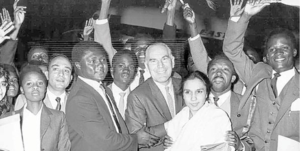

In 1979, it was finally time for the war to end. The Rhodesian government met with representatives from ZANU and ZAPU at the Lancaster House in London. There, spokesmen for Zimbabwe’s liberation movements, including Eddison Zvobgo, successfully negotiated with the British and Rhodesian governments for Zimbabwe’s liberation. Zvobgo and the other leaders of these independence-based political parties became heroes to the people of Zimbabwe. Zvobgo then went on the have a successful political career, building the very foundation of a new nation serving as Zimbabwe’s minister of local housing before being promoted to minister of justice. For twenty-one years, Zvobgo worked to help set Zimbabwe on the right path until he retired in the year 2000. Unfortunately, his well-deserved retirement would not last, as in 2004 he lost his battle with cancer. He was buried in Harare at Hero’s Acre, and his legacy will be well remembered by the grateful people of Zimbabwe.

Bibliography

Carry, Robert and Mitchel, Dianna. ”EDDISON JONAS MUDADIRWA ZVOBGO | African Nationalist Leaders – Rhodesia To Zimbabwe”. Colonialrelic.Com, 2022, http://www.colonialrelic.com/biographies/edson-zvobgo/ . Accessed 30 Mar 2022.

Andrew Meldrum “Obituary: Eddison Zvobgo”. The Guardian, 2004, https://www.theguardian.com/news/2004/aug/24/guardianobituaries.zimbabwe. Accessed 7 Mar 2022

Zvobgo, Eddison. “Letter to the UN from the National Democratic Party of Southern Rhodesia” 1961

“Political detainees and the liberation struggle: Part Three …a look at Sikombela and Wha Wha detention centres” 2015 https://www.thepatriot.co.zw/old_posts/political-detainees-and-the-liberation-struggle-part-three-a-look-at-sikombela-and-wha-wha-detention-centres/

Picture Citations

https://rangamberi.tumblr.com/post/98956111419/a-time-to-rise-edison-zvobgo

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eddison_Zvobgo

https://blogs.fcdo.gov.uk/stories/lancaster-house-inside-the-house-that-made-history/

“A World Struggle, A Human Struggle.” – Tom Mboya

The story of Tom Mboya and Martin Luther King Jr.’s first meeting.

Joshua Prieto

May 2, 2022

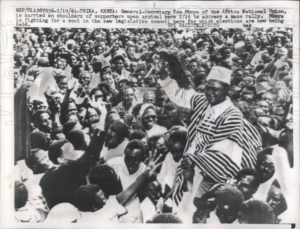

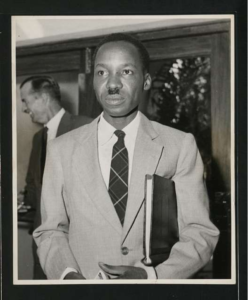

Image: Tom Mboya

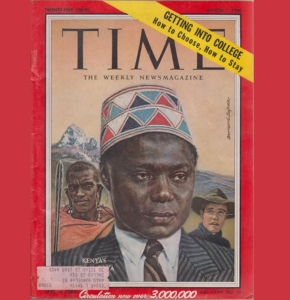

Tom Mboya was an influential politician in Kenya. He worked extensively to create workers and trade unions in Kenya. He helped secure Kenya’s independence and became an active member of the government. Mboya held positions as the minister of labor and, later, as Economic planning minister. Mboya had close relations with many political figures in the USA.

On April 18th, 1959, Tom Mboya spoke during a march on Washington in support of the implementation of the Brown V. Board of Education decision. He gave a speech to nearly 20,000 people with other speakers like Martin Luther King and Roy Wilkins. https://youtu.be/DfvFNRRfAxE

The main mission of Mboya’s US tour was to begin fundraising and gaining support for his Student Airlift program. The program allowed African students the chance to study at American Universities.

Tom Mboya landed in Atlanta and was welcomed by Ralph Abernathy, Horace Mann Bond, Martin Luther King, and Rufus Clement.

Mboya gave a speech during the “African Freedom Dinner” and talked with Martin Luther King Jr. King also gave a speech during this dinner.

Mboya and King began a brief correspondence after their meeting.

On 16 June, shortly after attending an SCLC-sponsored “Africa Freedom Dinner,” Kenyan nationalist leader Mboya wrote King requesting financial assistance for a Kenyan student who was to enter Tuskegee Institute in the fall. King responded, praising Mboya’s work in Kenya. He thanked Mboya for his praise and commented on the similarities their movements for freedom had, stating ” I am absolutely convinced that there is no basic difference between colonialism and segregation.” He then affirmed that he would help fund the education of an African student.

Letter from Martin Luther King, Jr. to Tom Mboya: https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/king-papers/documents/tom-mboya

Tom Mboya’s trip to the US was very important in shaping his political future. He met with many influential Americans involved in civil rights and politics.

Mboya met with influential American figures before his return to Kenya.

Tom Mboya even met his future wife during his US tour while she was attending an American University. Mboya married Pamela Odede and raised five children in Kenya. They were together until Tom Mboya’s assassination in 1969.

Mboya, and others, work to fundraise and support the Airlift program was successful. Between 1959 and 1962, over 700 students were able to go to the US for education. This allowed well-educated Kenyans to return and help Kenya organize and develop a stable government.

Bibliography.

Mboya Visits the U.S.

Houser, G. M. (1959). Mboya Visits the U.S. Africa Today, 6(3), 9–11. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4184012

Remarks delivered at Africa Freedom Dinner at Atlanta University

Remarks delivered at Africa Freedom Dinner at Atlanta University. The Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute. (2021, May 24). Retrieved May 2, 2022, from https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/king-papers/documents/remarks-delivered-africa-freedom-dinner-atlanta-university

Letter to Tom Mboya

To Tom Mboya. The Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute. (2021, May 24). Retrieved May 2, 2022, from https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/king-papers/documents/tom-mboya

African American Students Foundation

African American Students Foundation. African Activist archive. (n.d.). Retrieved May 2, 2022, from https://africanactivist.msu.edu/organization.php?name=African%2BAmerican%2BStudents%2BFoundation

Thomas Mboya (Joseph Odhiambo) (1930-1969)

Hegazy, A. (2011, January 16). Thomas Mboya (Joseph Odhiambo) (1930-1969) •. •. Retrieved May 2, 2022, from https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/mboya-thomas-joseph-odhiambo-1930-1969/

Airlifts of US: The first Kenyans to study in America

The East African. (2016, December 2). Airlifts of US: The first Kenyans to study in America. Retrieved May 2, 2022, from https://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/tea/magazine/airlifts-of-us-the-first-kenyans-to-study-in-america-1358684

Tom Mboya: Labor organizing and the struggle for Kenyan Independence

Zachary Jordan

May 4, 2022

Mboya was born in 1930, and spent much of his early years living on a sisal plantation with his parents, where his father earned around £2.13 per month. Though it wasn’t much, it was enough to pay for his education, as he attended several different mission schools throughout Kenya as a young boy. He was Suba, a multi-ethnic group within Kenya drawn from various tribes, but he most closely associated with his Luo ethnic roots, with his parents both born on Rusinga Island. 1

He would attend various mission schools throughout his childhood, moving between Kamba and Luo lands as he went. Though he never particularly excelled in school, his grades were good enough for him to continue his education in Nairobi, where he began studying as a teacher but quickly took on training as a sanitation inspector, a position that would afford him many opportunities.

While working in Nairobi, Mboya began to witness inequality and experience racism to a much greater degree than ever before, being paid 1/5 the salary of White colleagues and given a completely different set of requirements. It was at this time that he became involved with the Kenya African Union and started looking up to freedom fighters like Jomo Kenyatta. Though the Labour Department was consistently strict with labor unions, in 1953 they granted official recognition to the Kenya Local Government Workers Union, an organization in which Mboya held a high position.

As Mboya’s political power in Kenya grew, so too did his relations with Western governments. In the mid 1950s, he traveled to the U.S., with one of his primary goals being “[raising] special funds […] to support projects in Africa to establish inter-racial co-operation.” He was a guest speaker for the American Committee on Africa (ACOA) in New York, and met with key figures of the AFL-CIO like Maida Springer Kemp, George Meany, and A. Philip Randolph in order to secure these funds for the Kenya Federation of Labour (KFL).

Image: Tom Mboya letter to George Meany (AFL-CIO president)

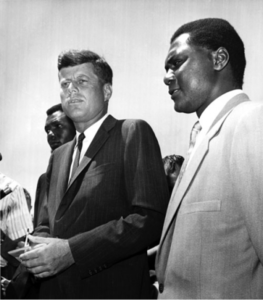

Continuing into the late 1950s and early 1960s, Mboya’s involvement with the U.S. deepened. In the American public eye, his statesmanship was commended: he met with prominent U.S. figures like Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and John F. Kennedy to bolster U.S.-Kenya relations and offer support to the Civil Rights Movement, and his airlift project gave Kenyan students opportunities to pursue university education in the U.S. Through private meetings and public speeches, he was given heroic treatment among many American audiences.

Tom Mboya on Meet the Press, April 1959 https://youtu.be/xeLHxFT6ojs

Image: John F. Kennedy and Tom Mboya

Less well-known at the time, however, were his close links to the CIA, for whom he was a key asset within Kenya. As a powerful figure (the general secretary of the KFL after 1953), a nationalist hero, and a supporter of foreign investment and land ownership in Kenya, Mboya was seen by the CIA as both strategically useful and significantly “safer” than Jomo Kenyatta, the main hero of Kenyan nationalism at the time. Many of his travels were funded by the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU), an organization aimed, in part, at countering left-wing trade unionism, a group for which Mboya later became a regional representative. Direct monetary support was also given to the KFL, as it was seen as a model “free trade union”: advocating workers’ rights without threatening free trade and international investment.

Mboya’s perception within Kenya was much more complicated than his generally positive reception within the U.S. As mentioned above, many Kenyans saw him as somewhat of a hero, as the KFL, in which Mboya was the general secretary, was a key leader in the independence movement following the banning of all other African political organizations in the midst of the Mau Mau uprising. His student airlift project, as well, was quite popular within Kenya.

Image: Students from one of the “airlifts” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Kennedy_Airlift)

In political circles, however, he was a much more controversial figure. His vying for power, as well as his favorable attitude towards the U.S., fostered bitter rivalries. One of his more staunch critics was Oginga Odinga. Despite their close associations and alliances during the 1950s, throughout the 1960s the two competed for President Jomo Kenyatta’s favor and argued frequently and publicly over the course of the newly independent Kenya’s future. Odinga favored closer alignment with the Soviet Union, while Mboya favored relations with Western nations and business interests.

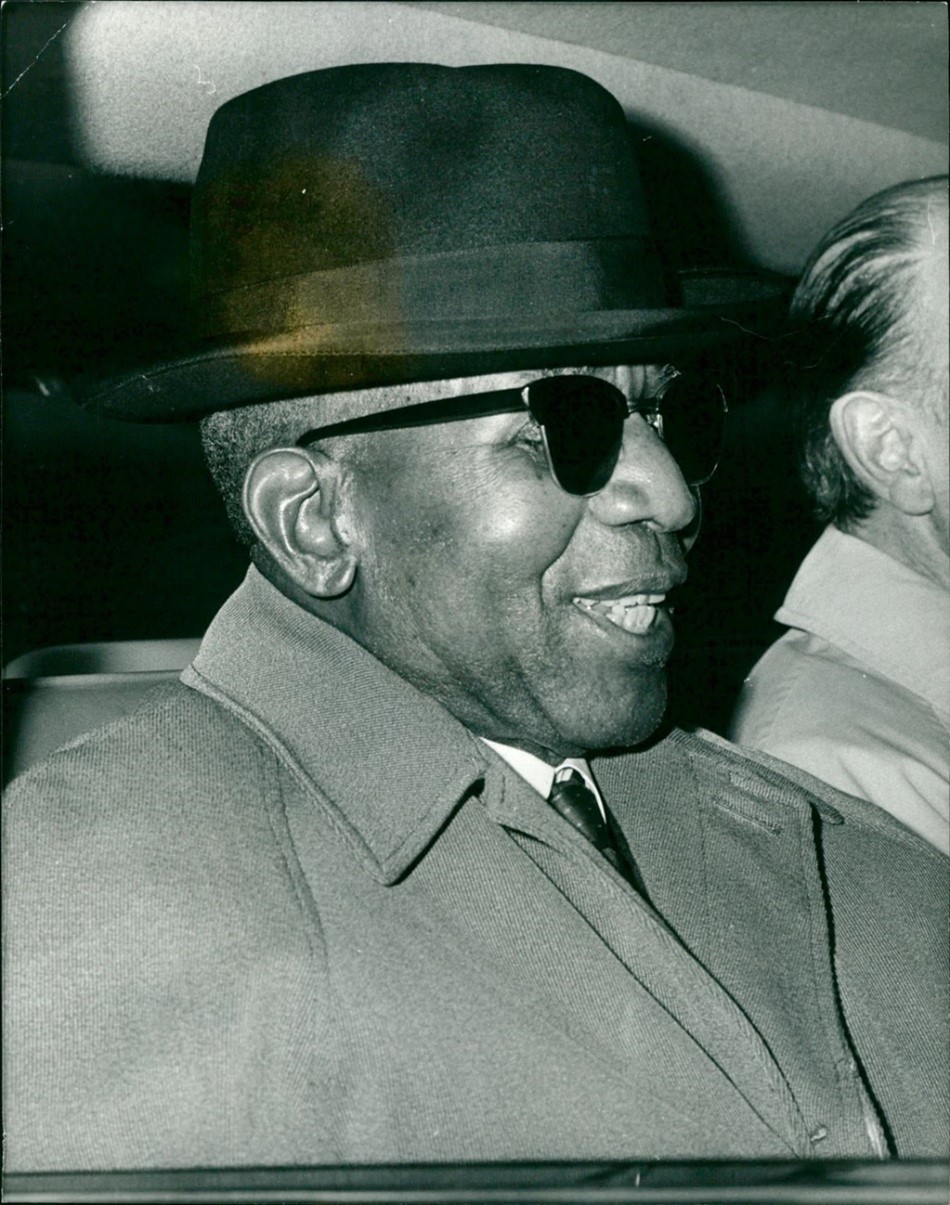

Oginga Odinga

An example of the contrast between his perception abroad and within Kenya; this is, of course, a simplification, as he did have supporters at home and detractors abroad.

Bibliography

David Goldsworthy, “Sisal and Schooling,” in Tom Mboya, the Man Kenya Wanted to Forget (Nairobi: Heinemann, 1982), pp. 4-9.

The CIA’s Global Strategy: Intelligence and Foreign Policy. (Cambridge, MA: Africa Research Group, 1971).

Julius Nyerere

Political Ideology as Told Through his Speeches

Hudson Hohman

May 4, 2022

Nyerere’s Political Ideology:

1) Supporter of Decolonization and African Nationalnist

2) Foriegn Policy: Close ties with Eastern powers especially China

3) Socialism and Ujamaa

4) Human Development / Supporter of Education

5) Ran a One-Party System Dictatorship While Simultaneously Calling for Democracy

6) African Unionist

<iframe width=”827″ height=”465″ src=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/q_gEGEJpxZg” title=”Rare Footage of Julius Nyerere at the UN General Assembly IN 1961″ frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share” allowfullscreen></iframe>

1) Supporter of Decolonization

UN Speech: December 14, 1961

Julius Nyerere spoke to the UN at the meeting discussing the admittance of Tanganyika into the assembly. Nyerere thanks both the UN and the United Kingdom for their help and support that allowed for their peaceful independence. He labels himself a nationalist and calls for the liberation of all African colonies.

“No country is completely free if it keeps other people in a state of unfreedom”

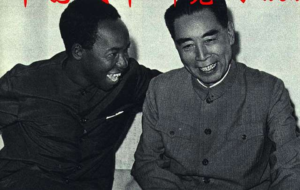

Nyerere with a Chinese official on a visit to China in 1965

2) Foreign Policy: Close ties with Eastern powers especially China

Relations With the West / East:

In his speech during the Commonwealth conference on June 23, 1965, Nyerere focused on African relations with the Western bloc and their commitment to democracy. He thanked England for their support during their independence movement. Upon being asked about his relations with the East, Nyerere admitted to accepting help from communist countries, mainly China. He also challenged England and other European countries that challenged his commitment to liberal democracy. Nyerere turned the question back on England and pointed out their continued support of Portugal in their racist colonial regime in Southern Rodesia.

“You are not being neutral if you continue to sell arms and other economic weapons to Portugal on the grounds that she is a member of NATO while Portugal is using her arms and such economic strength as she has in an effort to retain control over her colonies.”

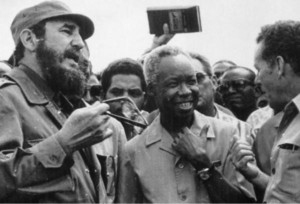

Nyerere with Fidel Castro, the leader of Cuba

3) Socialism and Ujamaa

Arusha Declaration: April 29, 1967

One of the most significant moments in Nyerere’s presidency was the introduction of the Arusha Declaration. While this is not a speech, the conditions were deliberated by the National Executive Committee, and the Declaration outlines Nyerere’s vision for the country. Nyerere had spent most of 1962 traveling the country and developing his political ideology of “Ujamaa” which is a form of African socialism. The work is broken into five different parts; the declaration describes a clear plan for Tanganyika. Part I: The beginning establishes the one party of the state’s mission and ideology. It primarily concerns equality and building a socialist state. The next part explains their socialist policies, which place the means of production in control of the government and workers. Part three emphasizes the importance of a self-reliant state and the development of the people within to achieve that goal. It focuses primarily on educating and developing peasants: Parts four and five detail TANU membership and the organization of the government and its party.

4) Human Development / Supporter of Education

The Power of Teachers: August 27, 1966

Julius Nyerere deeply believed in the benefits of education. An important piece of the Ujamaa ideology was human development, especially through early education. Through his policy, he implemented universal primary schooling throughout his country. Tanzania also boasted one of the highest literacy rates on the African continent at the time. His speech given at the opening of the Morogoro Teachers’ College not only shows his dedication to creating the conditions for proper schooling but also his passion for teaching. His nickname “Mwalimu” means teacher. In his speech, he praises the new crop of educators and ensures they know just how important they are to the future of their country.

“The truth is that it is teachers more than any other single group of people who determine these attitudes and who shape the ideas and aspirations of the nation.”

5) Ran a One-Party System Dictatorship While Simultaneously Calling for Democracy

6) African Unionist

Interview in 1966:

Nyerere discusses his views on having a one-party democratic system. He explains that people in the West think that democracy cannot exist in a one-party system. Julius disagrees and says his people feel that they have power within their government. Nyerere actually believed that the one-party system provided a more democratic system for his people. He spoke on the union with Zanzibar. Nyerere believed the two states were equal despite their disparity in size and population. Finally, he explained his vision for a United East Africa and ultimately why the idea failed. The prospect of an African republic was made more difficult because the states were developed independently.

“In East Africa, we should have become united before we became independent before we became separate states.”

Bibliography

Bjerk, Paul. Julius Nyerere. Ohio University Press, 2017.

Nyerere, Julius K. Freedom and Socialism. Uhuru Na Ujamaa; a Selection from Writings and Speeches, 1965-1967. Oxford University Press, 1971.

The Defiance Campaign

The Power of the People

Myles Rosenblum

May 4, 2022

National Party

On May 26th, 1948, D.F. Malan’s National Party, which was allianced with N.C. Havenga’s Afrikaner Party, barely won with a five-seat majority and only 40% of the overall electoral votes. The National Party that came to power was essentially two parties that combined together. One party was rooted in white supremacy and introduced apartheid. The other party was a nationalist party appealing to Afrikaans culture by establishing a common history and a hatred of Britain.

A Shift in the ANC

After the National Party came into power, the African National Congress (ANC) began abandoning its traditional reliance on tactics of moderation such as petitions and deputations. In December 1949, with the support of the ANC Youth League, a new leadership came to power in the ANC. Walter Sisulu was elected secretary-general and a number of Youth Leaguers were elected to the national executive, including Oliver Tambo, Sisulu’s successor. These young minds brought completely different approaches to past problems.

Moderation to Mass Imprisonment

https://www.sahistory.org.za/arch

There is a shift from the older generation of the ANC, who would fight with petitions, speeches, and education, to a more militant younger group of the ANC. This younger group was interested in overcrowding the prison system through civil disobedience.

Separate Representation of Voters Act

“the removal of all Cape Coloureds from the present electoral roll; the drawing up of a new electoral roll for Coloured males able to meet the existing literacy and property qualifications; the holding of separate elections for those on the Coloured roll to select four Whites to represent them in the House of Assembly, one in the Senate and two in the Cape Provincial Council; the establishment of a Board of Coloured Affairs to advise the government on Coloured matters and to act as an intermediary between the Coloured community and the government. The II-member board would be under the direction of a White commissioner and would be made up of eight Coloureds elected in the Cape, and three nominated by the government to represent Natal, the Orange Free State and the Transvaal.”

This blatantly racist act acted as a tipping point in the ANC’s response to the National Party. It was after this act was passed that the younger members of the ANC decided an organized protest must follow.

National Day of Pledge and Prayer

On April 6th, 1952, while white South Africans celebrated the 300-year anniversary of Jan van Riebeeck’s arrival at the Cape in 1652, the ANC and SAIC called on black South Africans to observe the day as a “A National Day of Pledge and Prayer”. The majority of Black adults and school children boycotted the festivities.

Day of Volunteers

On June 22nd, 1952, the Sunday before the Defiance Campaign officially began, volunteers signed a pledge:

“I, the undersigned, Volunteer of the National Volunteer Corps, do hereby solemnly pledge and bind myself to serve my country and my people in accordance with the directives of the National Volunteer Corps and to participate fully and without reservations to the best of my ability in the Campaign for the Defiance of Unjust Laws. I shall obey the orders of my leader under whom I shall be placed and strictly abide by the rules and regulations of the National Volunteer Corps framed from time to time. It shall be my duty to keep myself physically, mentally and morally fit.”

Defiance Campaign

On June 26th, 1952 the Defiance Campaign officially began in Bloemfontein. “For the first time Africans and Indians, with a few whites and coloureds were engaging in joint political action under a common leadership.”

The Growth of the Campaign

The first march was a small group into Boksburg (near Johannesburg) without permits. The group, which included Nelson Mandela and Walter Sisulu, were all arrested and thrown in jail. This was their goal. News spread and soon groups were marching into “Europeans Only” entrances of railway stations, post offices, and other public areas.

Numbers

During the last few days of June, 146 volunteers were arrested.

July: 504 volunteers

August: 2,015 volunteers

September: 2,058

By December another 2,334 volunteers were arrested.

Total: 8,057 volunteers in less than six months were arrested.

Global Significance

One of the many global effects of the Defiance Campaign was its influence on the Civil Rights Movement in the United States. Civil disobedience and peaceful protests are direct actions taken from the ANC. The video above clearly shows the success of the bus boycotts in South Africa. The infamous photo of Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycotts shows how far-reaching the ANC’s protest tactics truly were.

Global Reaction

While the overall goal of systematically dismantling apartheid was not achieved, the Defiance Campaigns were successful both nationally and on a global scale. The Defiance Campaign shined a light on the terror in South Africa and forced the United Nations to recognize that the South African racial policy was an international issue. In addition, a UN Commission was established to investigate how to address the “situation” in South Africa.

Bibliography

“Freedom For My People”, Z.K. Matthews, Cape Town: Collings, 1981. (Published posthumously in 1981)

“Foreword”, in Responsible Government in a Revolutionary Age, [ed.] Z. K. Matthews, Association Press, New York, 1966.

“Exchange of Correspondence between the African National Congress, the South African Indian Congress, and the Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa between 21 January and 20 February 1952” By D.U. Mistry, Y.A. Cachalla, Y.M. Dadoo, M. Aucamp, W.M. Sisulu, J.S. Moroka.

“Campaign of Defiance against Unjust Laws – Document Collection”.

“Apartheid in South Africa – Documentary on Racism, Interviews with Black and Afrikaner Leaders. 1957.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wdlD-Q9wmfY

“Separate Representation of Voters. Act #46, 1951. Enacted by the Parliament of South Africa.”

The Sports Boycott

By Sara Hagstrom

May 2, 2022

Apartheid and Sports

The legal policy of Apartheid was put into place in South Africa after the Afrikaner National Party came into power in 1948, The policy of Apartheid was comprised of a series of segregation policies that segregated all aspects of South African life and promotes the power of the white minority.

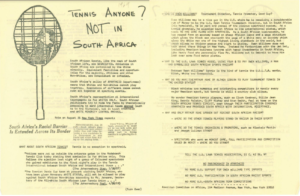

https://projects.kora.matrix.msu.edu/files/210-808-10943/Binder3.pdf

This leaflet, produced by ACOA, details how the policy of apartheid prohibits white tennis players and non-whites tennis players from playing together. As a result of white control over sports in South Africa, there are few facilities and opporunities for non-whites to play tennis . It also exposes the South African government’s practice of sending interracial teams to international competitions, such as the Olympics, in attempts to appear racially inclusive.

In this document by the United Nations Centre Against Apartheid, Prime Minister Vorster discusses South Africa’s policy change that recognizes racial groups in South Africa as a “nations.” This allows South Africa to claim that they allow integrated competition in open international competitions; however, they could not compete as an integrated team. He comments on the fact despite this policy change to appear less segregated, the policy of multi-nationalism provided little to no change on the inequalities in sports for non-whites.

The Sports Boycott

As the anti-apartheid movement increasingly gained momentum in the late 1950s, the international community sought to condeM.N. the racially restrictive laws of apartheid. In response to the influence of apartheid policies in sports in South Africa, many countries began to boycott South African sports in attempts to fight against racial segregation and pressure the South African government to reform their oppressive policies. The sports boycott also involved the banning of South Africa from numerous international events, such as the Olympic Games.

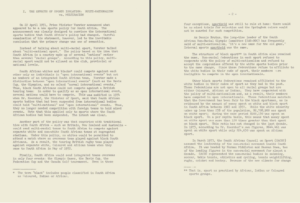

As President of the South African Non-Racial Olympic Committee (SAN-ROC), Dennis Brutus protests against not only the 1977 Davis Cup, but the support of all sports events that allow South Africa to participate. He argues for a sports boycott in order to protest against South Africa’s racist policies.

This press release from ACOA details the contents of a letter written by 30 prominent American athletes, civil rights leaders, union leaders, etc. to the President of the U.S. Olympic Committee. In this letter, they urge the President to prevent South Africa’s participation in the 1968 Olympic Games due to their discriminatory, segregationalist practices. This letter is just one example of the efforts made during the sports boycott against South African sports.

The Davis Cup 1977

https://projects.kora.matrix.msu.edu/files/210-808-7292/protestdaviscupleaflet.pdf

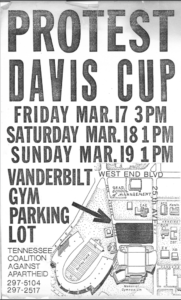

Tennessee Coalition Against Apartheid leaflet advertising the protest of South Africa participating in the Davis Cup.

https://projects.kora.matrix.msu.edu/files/210-808-7311/acoadontplay.pdf

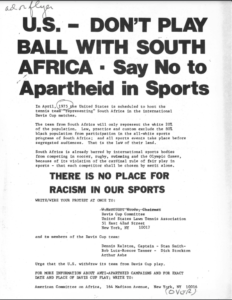

In this leaflet, ACOA urges the U.S. to withdraw from the Davis Cup because South Africa’s sports policy does not align with fair play practices.

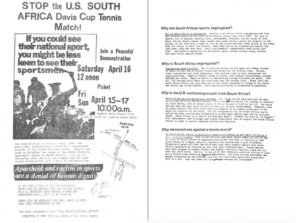

The Organization of African Unity fight against the Davis Cup, in which the US would play with South Africa; thus supporting Apartheid and racism in sports.

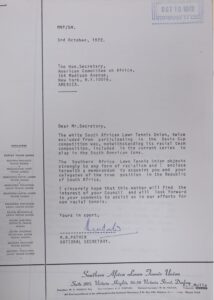

M.N. Pather writes on behalf of the South African Lawn Tennis Union (SALTU) to ACOA asking them for assistance the union’s goals of against racism and Apartheid. He expresses his concern about the fact that the white South Africa Lawn Tennis union was excluded from the Davis Cup due to their segregated team, but were still being allowed to play in South American competitions.

As one of the most prominent African American tennis players at the time, Ashe’s support of the anti-apartheid movement in the realm of sports was highly influential. However, he opposed the sports boycott because he held the belief that isolating South Africa from the rest of the world would prolong Apartheid segregation laws.

As general secretary of SACOS and SALTU, two anti-Apartheid organizations in South Africa, Pather played a large role in the success of the sports boycott. Through his work with the anti-apartheid movement, he never failed to uphold his belief that there is “no normal sport in an abnormal society”; meaning desegregation in sports cannot be achieved until all anti-apartheid legislation is removed. 1

American Committee On Africa

ACOA plays a huge role in promoting the international sports boycott of South African sports. The association took many actions and published numerous pamphlets and press releases advocating for importance of participation in the boycott in addition to supporting the anti-apartheid movement in various other sectors.

A Letter to Arthur Ashe: From M.N. Pather

In 1973, M.N. Pather wrote a letter to Arthur Ashe, requesting him to decline the offer to play in the South African Open Championships. He informs Ashe that interracial tennis does not exist in South Africa despite the government’s new law of multinationalism.

Despite Pather’s letter and request that he decline the invitation to the South African Open Championships, Ashe still accepts the invitation to play in the tournament. In response to Pather’s letter, Ashe writes a letter in return, explaining why he decided to participate in the championship. He stated, “I, more than ever, think that the further contact with the politically active American blacks is essential to speed up South Africa’s transition to normalcy.”

In response to Ashe’s letter, Pather expressed that he regarded Ashe as naïve to the magnitude of racial division in South Africa, which furthered his belief that the façade of the multinational sports policy prohibited movement towards nonracial sports and solidified his overall commitment to his work.

Significance of the Sports Boycott

The sports boycott of South African sports was significant because of the importance and centrality of sports to the white South Africans. “Their exclusion from the international arean was more widely felt than the other academic, cultural, and economic sanctions.” Thus, the sports boycott played a large role in the greater anti-apartheid movement. Additionally, the activism connected to the sports boycott also provided greater awareness about apartheid laws and provided much needed support and power to anti-apartheid groups at the time.

Bibliography

Arsenault, Raymond. Arthur Ashe: A Life. United Kingdom: Simon & Schuster, 2019.

Barnes, Catherine. “Incentives, Sanctions and Conditionality,” International isolation and pressure for change in South Africa | Conciliation Resources, February 1, 2008, https://www.c-r.org/accord/incentives-sanctions-and-conditionality/international-isolation-and-pressure-change-south.

Bersell, Matt. “Sports, Race, and Politics: The Olympic Boycott of Apartheid Sport.” Western Illinois Historical Review, 2017. http://www.wiu.edu/cas/history/wihr/pdfs/wihr-sports-race-politics-olympic%20boycott.pdf.

Chen, Teddy. Arthur Ashe Addressing the Special Committee on the Policies of Apartheid of the Government of the Republic of South Africa. Photograph. New York, April 14, 1970. https://africanactivist.msu.edu/image.php?objectid=210-809-847.

Childress, Contributor: Boyd. “Arthur Ashe (1943–1993).” Encyclopedia Virginia, July 10, 1943. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/ashe-arthur-1943-1993/.

Davis Cup – Protest against South African Participation. Photograph. Nashville, Tennessee, March 17, 1978. https://africanactivist.msu.edu/image.php?objectid=210-809-77.

George Houser Receives Gift at ACOA 25th Anniversary. Photograph. New York, November 12, 1978. https://africanactivist.msu.edu/image.php?objectid=210-809-1877.

Govender, Subry. “Activist Gave South Africa a Level Playing Field.” PressReader.com – Digital Newspaper & Magazine subscriptions, August 20, 2020. https://www.pressreader.com/south-africa/the-mercury-south-africa/20200820/page/6/textview

Govender, Subry. “‘Don’t Play Here, Ashe Urged.” The Daily News. November 9, 1973.

M.N. Pather. n.d. Photograph. https://photos.geni.com/p8/8748/7633/534448377d722e0d/M.N._PATHER_medium.jpg.

The Sharpeville Massacre

Samuel Panoff

Spring 2022

One of the deadliest events throughout apartheid South African history, the Sharpeville Massacre left 69 dead during a peaceful protest.

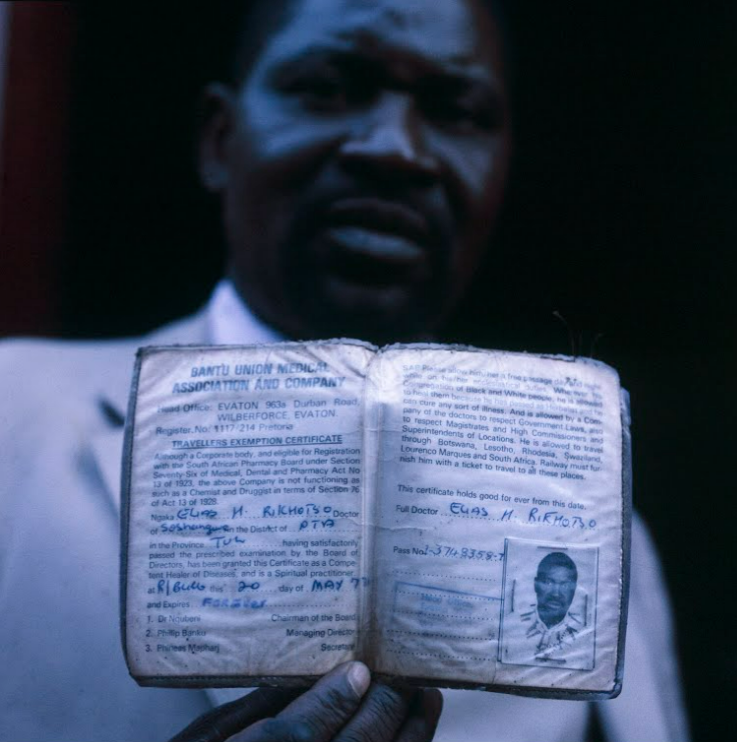

Pass Laws

The Pass Laws Act was established in 1952 and was used to keep control of the African population in South Africa. This law required all African residents to carry around a “reference book” that contained information about the carrier. Police would use these books as an excuse to fine and arrest African citizens who did not qualify for them.

Idea of Peaceful Protest

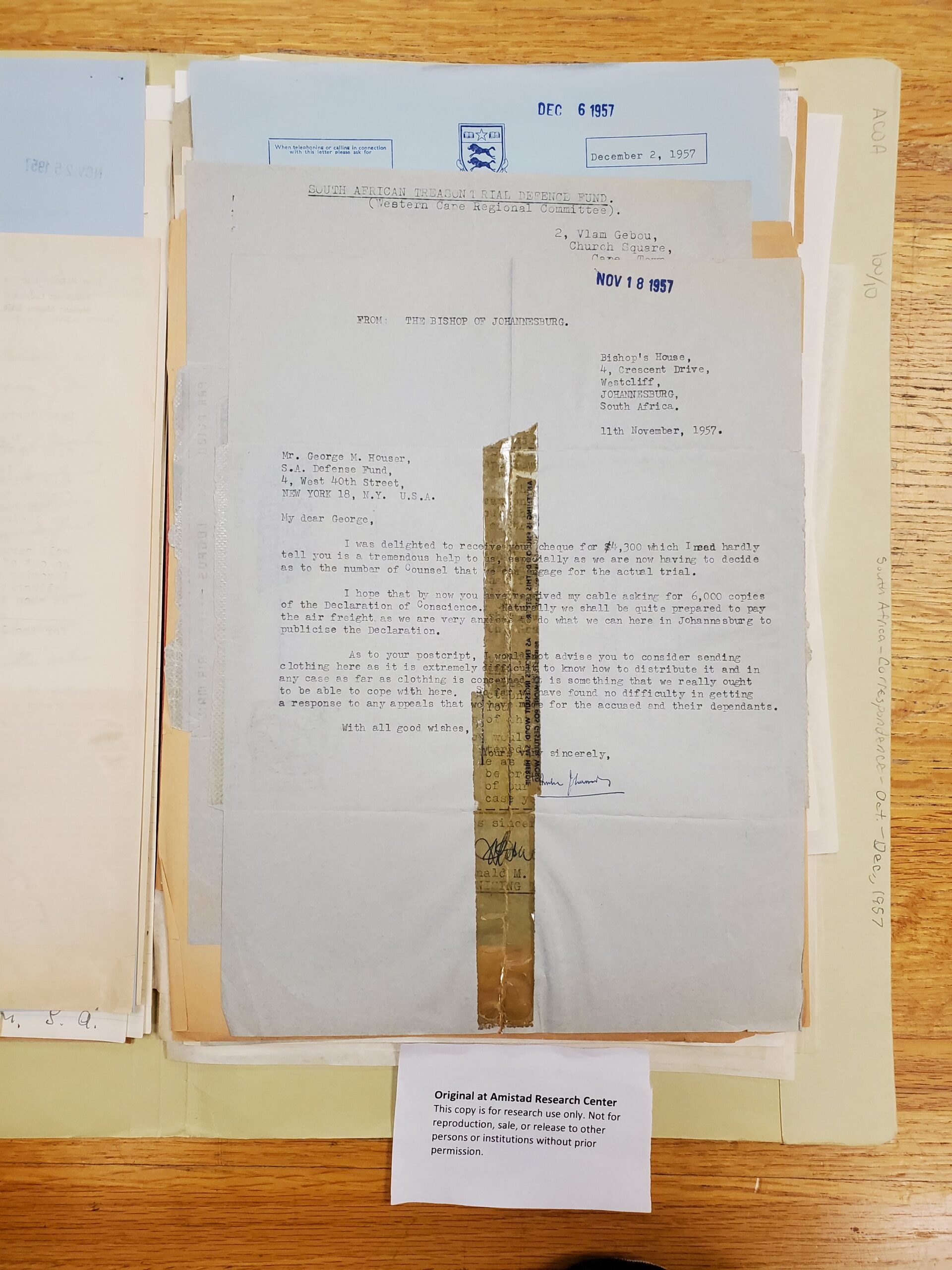

African citizens used a variety of means to oppose apartheid laws. Organizations such as the PAC and ANC staged peaceful protests and boycotts. They would teach citizens the idea of fighting in a nonviolent way. These tactics were used for years pertaining to many unjust laws in South Africa.2 Ambrose Reeves used the Declaration of Conscience to teach his African neighbors the ideas of the right to criticize and protest.3

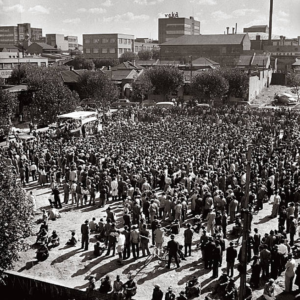

The Protest

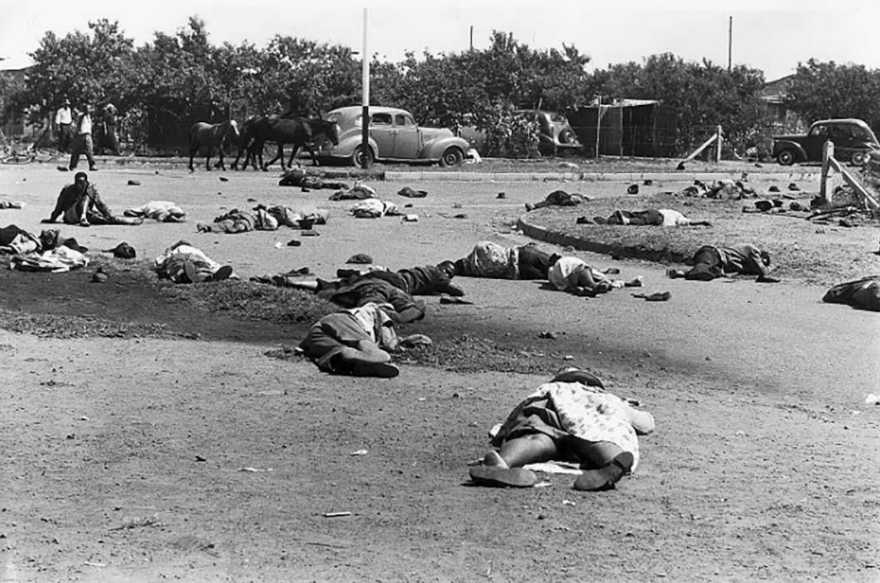

In March 1960, the PAC organized a peaceful protest in the black township of Sharpeville, where people would come to object and burn their reference books. The tone of the protest was cheerful, as protestors carried signs and thousands chanted for the pass laws to be abolished. It took a turn for the worse when police showed up.4

The Shooting

Throughout the protest, swarms of police and armored vehicles began to occupy the area. They pointed their guns at the large crowd and started to open fire. Many of the protestors were shot in their backs as they were trying to escape the scene. In the end, sixty-nine African protestors were killed, and hundreds were injured.5 Lydia Mahabuke, one of the protestors, felt a shot in her back while trying to escape. “After having felt this, I tried to look back. People were falling, scattered. There was blood streaming down my leg. I tried to hobble. I struggled to get home.”6

Domestic Response

There were mass funerals for the victims, yet within the township of Sharpeville, there was no response to the event, as people who spoke against the government were detained by the police. There were a variety of responses from different leaders and organizations in South Africa. Figures such as Nelson Mandela and Chief Albert Luthuli burned their passbooks in protest. There were also countless protests, including a large-scale one with tens of thousands of people in Cape Town. The government would eventually call for a state of emergency and ban any sort of gathering.7

Ambrose Reeves also tried to help by rushing to hospitals around Sharpeville to interview some of the injured protectors. He hoped that these accounts would help bring national attention to this tragic event.8 Reeves would end up being arrested and exiled from South Africa due to his vocal protest of the South African government.

International Response

There was an array of international response by various countries. The United Nation called for the abolition of apartheid and condemned the massacre on April first. Within the coming months, the UN declared that apartheid was a violation of their charter and placed economic sanctions on South Africa. Though their government became isolated after this event, it did not stop them from continuing to administer apartheid law.9

Conclusion

Though the Sharpeville Massacre brought the horrors of apartheid to the eye of the international world, it didnot stop the South African government. In the months following the massacre, thousands of Africans would bearrested for protesting the government, and groups such as the ANC and PAC were banned. It would take yearsofboth violent and nonviolent protest, along with international pressure for apartheid to finally come to an endthirty years later. The Sharpeville Massacre is an atrocious part of South African history, but it is important toremember about this and othersimilar moments to make sure it never happens again.

Bibliography

2. Matthew Mcrae, “The Sharpeville Massacre,” CMHR, n.d.

3. Ambrose Reeves, letter to George M. Houser, 11th November, 1957

4. Matthew Mcrae, “The Sharpeville Massacre,” CMHR, n.d.

5. Matthew Mcrae, “The Sharpeville Massacre,” CMHR, n.d.

6. Matthew Mcrae, “The Sharpeville Massacre,” CMHR, n.d.

7. “Aftermath: Sharpeville Massacre 1960 – Sahistory.org.za,” South African History Online, June 13, 2011.

8. Ambrose Reeves, “The Sharpeville Massacre – a Watershed in South Africa,” n.d.

9. “Aftermath: Sharpeville Massacre 1960 – Sahistory.org.za,” South African History Online, June 13, 2011.

M.W. Kanyama Chiume Revolutionary and Enemy of the Revolution

Revolutionary and Enemy of the Revolution

Mira Fechter

May 4, 2022

November 22, 1929

Murray William Kanyama Chiume is born in Usisya Village, Nkhata Bay District, Malawi.

1944

Chiumemoves to Dar es Salaam, Tanganyika (now Tanzania) to attend school.

1949

Chiume is admitted to Makerere College in Kampala, Uganda, a prestigious university atwhich Chiume would study medicine.

1951

Kanyama Chiume abandons medicine because he “could notstand human dissection.” Hewent on to study education, specializing in physics, chemistry, and biology.

1953

Chiume attends Ramjas College in Delhi to study law.

1956

Chiumeabandons his education after being asked to stand for Nyasaland’s first elections in1956.

1957-1961

Chiume is active in the Nyasaland African Congress and in organizing and mobilizing thenationalist movement with Nyasaland.

1962

Chiume is appointed Minister of Education, and once the government is officially formed, heis moved to the post of Foreign Minister.

1964

Nyasaland achieves its official independence, and the country is named “Malawi” by the newPresident, Dr. Hastings Banda, to whom Chiume washis closest advisor.

Song sung at independence

Tiyende pamodzi ndi mtima umodzi! (Let’s march forward in one spirit!)

Tiyende pamodzi ndi mtima umodzi (Let’s march forward in one spirit)

Eee, A Banda tiye! Tiyende pamodzi! (Banda, let’s march!)

A Chipetiye! Tiyende pamodzi! (Chipe, [Chipembere] let’s march!)

Tiyende pamodzi ndi mtima umodzi (Let’s march forward in one spirit)

Eee, A Chirwa tiye! Tiyende pamodzi! (Chirwa, let’s march!)

Kanyama tiye! Tiyende pamodzi! (Kanyama, let’s march!)

Tiyende pamodzi ndi mtima umodzi (Let’s march forward in one spirit!)

Image: Hastings Banda

Banda’s young life in Nyasaland, education at prestigious universities such as University of Chicago and University of Edinburgh, and outspoken opposition to the CAF made him a premier candidate for leader of the Nyasaland African Congress and later Prime Minister of the fledgling government of post-colonial Nyasaland, two roles which he ultimately accepted, and ones that Kanyama Chiume strongly lobbied for.

Moto! Moto! Wayaka! (Fire, fire is ablaze!) Moto, wayaka! Moto, wayaka! (Fire is ablaze! Fire is ablaze!) A Malawi? (Malawians?) Amalawi safuna: (Malawians don’t want:) Chipembere, Kanyama (Chipembere, Kanyama,) Willie Chokani! (Willie Chokani!)

“He banned women from wearing trousers or mini-skirts. He prohibited kissing in public. He ordered haircuts for long-haired tourists. He banned bell-bottom jeans and banned over-the-collar haircuts for men as he considered them a sign of decadence. He censored the mail, jailed his opponents, declared himself President-for-Life and ruled Malawi for three decades until the age of 96.”

International Response to Apartheid From 1960-1980

Jack Marcou, Rachel Smith, and Ali Williams

Fall 2021

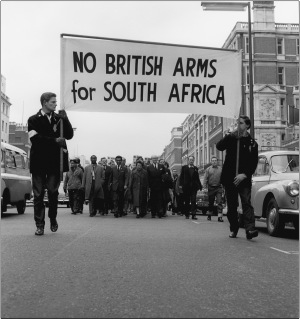

trials that hindered the opportunity for peaceful demonstrations. With few options left at their disposal, a multitude of pro–liberation organizations worked within their networks to launch a campaign for the boycott of South African products. While left–wing political organizations had moderate success on a national level, it became clear as 1960 approached that the expansion of the boycott system needed to be implemented in Britain and throughout the globe. Britain was split as a nation regarding its attitude towards the South African government’s treatment of black Africans. Conservative ideology reflected the notion that Britain was largely dependent on South Africa as a trading and investment partner, and it was not their place to meddle in its internal affairs. On the other hand, Christian and left–wing Brits felt a moral obligation for the country to take a stance against racism and human rights violations. By the 1960s, the issue of South Africa had become mainstream in Britain, with many left–wing organizations acting against apartheid.

The movement’s goal was to get shoppers from all over the world to boycott apartheid products. This meant products from South Africa were not purchased. People who had never been a part of any meetings or protests showed their support by boycotting South African goods.

The CAO launched pickets and protests at shopping centers to encourage Britons to boycott purchasing items produced in South Africa. Demonstrators told shoppers, “Don’t Buy Slavery, Don’t Buy South Africa.”

One of the first moves for the boycott was boycotting fruits from South Africa. Leaders told shoppers to be mindful of the labels on the fruits, such as Tesco and Sainsbury’s. This eventually led to a campaign for stores to stop stocking South African products altogether. Activists were trying to make sure these shops understood the significance of this boycott and how the adverse effects could continue if they continued to carry these products. Another example was when a shop worker from Dublin refused to ring up a cape grapefruit which eventually led to a strike. To follow up on that was a total ban on all imports from South Africa by the Irish government. This shows how bold and determined these protesters were to make achange so much so they would refuse to ring a customer up, and in doing so, they succeeded. As time went by, all the protests and boycotts were successful, and it turned out to be one of the most successful anti–apartheid movement campaigns.

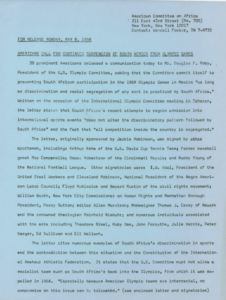

Three years after the Sharpeville Massacre, the United Nations took its first significant step towards stopping apartheid by creating the Special Committee on the Policies of Apartheid of the Government of the Republic of South Africa; the first meeting of the committee was on April 2, 1963. The committee later renamed the Special Committee Against Apartheid would become the UN’s primary mechanism for anti–apartheid action (“Special Committee Against Apartheid”). The committee quickly pushed through an arms and oil embargo the same year. In 1966 the committee organized the International Seminar on Apartheid in conjunction with the Brazilian government. It was a first–of–its–kind series of anti–apartheid talks and presentations held 23 August–4 September 1966.

The UN General Assembly also took actions against South Africa and their Apartheid Regime. This resistance primarily came in the form of a resolution and two conventions. On December 2, 1968, the assembly passed General Assembly resolution 2396, which condemned the South African government and requested states “to suspend cultural, educational, sporting and other exchanges with the racist regime and with organizations or institutions in South Africa which practice apartheid” (General Assembly resolution 2396).

did not enter into force until January 4, 1969. While it may not seem like a specific and direct attack on apartheid, the horrors in South Africa directly influenced the creation of this

convention (Heyns and Viljoen). The benefit of not making it overly specific was that the convention could also be applied to other decolonization efforts around the globe; the downside is it gave the convention even less power over apartheid specifically than it already had. The second convention the General Assembly passed was an attempt to ratify this. On November 30, 1973, the General Assembly adopted the International Convention on the Suppression & Punishment of the Crime of Apartheid; it did not go into effect until July 18, 1976. The convention openly calls apartheid “a total negation of the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations and […] a crime against humanity.” (General Assembly resolution 3068).

When none of these efforts worked, the General Assembly took a vote on November 12, 1974. With a vote of 91–22, the general assembly suspended South Africa from participating in the UN. This was not a complete suspension of membership, but rather the “[South African] delegation will not be permitted to take its seats, speak, make proposals or vote.” (Teltsch) This was a significant action in the international community and the capstone of a decade of UN condemnation of the Apartheid regime in South Africa.

Bibliography

General Assembly resolution 2396, The Policies of Apartheid of the Government of South Africa,

A/RES/2396(XXIII), (02 December 1968), available from

https://undocs.org/en/A/RES/2396(XXIII).

General Assembly resolution 3068, International Convention on the Suppression & Punishment

of the Crime of Apartheid, A/RES/3068(XXVIII), (30 November 1963), available from

https://documents–dds–

ny.un.org/doc/RESOLUTION/GEN/NR0/281/40/IMG/NR028140.pdf?OpenElement.

Gurney, Christabel. “‘A Great Cause’: The Origins of the Anti–Apartheid Movement, June 1959–

March 1960.” Journal of Southern African Studies 26, no. 1 (2000): 123–44.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/2637553.

Heyns, Christof and Frans Viljoen. “The Impact of the United Nations Human Rights Treaties on

the Domestic Level.” Human Rights Quarterly 23, no. 3 (2001): 483–535.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/4489346.

Rosen, Armin. “The Olympics Used to Be so Politicized That Most of Africa Boycotted in

1976.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 7 Aug. 2012,

https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2012/08/the–olympics–used–to–be–so–

politicized–that–most–of–africa–boycotted–in–1976/260831/.

“Special Committee Against Apartheid,” African Activist Archive, 2021,

https://africanactivist.msu.edu/organization.php?name=Special+Committee+Against+Apar

theid.

Teltsch, Kathleen. “South Africa Is Suspended By U.N. Assembly, 91‐22.” The New York Times.

November 13, 1974. https://www.nytimes.com/1974/11/13/archives/south–africa–is–

suspended–by–un–assembly–9122–un–session–barssouth.html.

“The United Nations in South Africa.” United Nations. 2021.

https://southafrica.un.org/en/about/about–the–un.

“The United Nations — Partner in the Struggle Against Apartheid.” United Nations. 2021.

https://www.un.org/en/events/mandeladay/un_against_apartheid.shtml.

Walker, Malcolm, and New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu Taonga. “The

African Boycott of the 1976 Montreal Olympics.” Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand –

Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand, Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu

Taonga, 11 Oct. 2016, https://teara.govt.nz/en/cartoon/37905/the–african–boycott–of–the–

1976–montreal–olympics.