By Sara Hagstrom

May 2, 2022

Apartheid and Sports

The legal policy of Apartheid was put into place in South Africa after the Afrikaner National Party came into power in 1948, The policy of Apartheid was comprised of a series of segregation policies that segregated all aspects of South African life and promotes the power of the white minority.

https://projects.kora.matrix.msu.edu/files/210-808-10943/Binder3.pdf

This leaflet, produced by ACOA, details how the policy of apartheid prohibits white tennis players and non-whites tennis players from playing together. As a result of white control over sports in South Africa, there are few facilities and opporunities for non-whites to play tennis . It also exposes the South African government’s practice of sending interracial teams to international competitions, such as the Olympics, in attempts to appear racially inclusive.

In this document by the United Nations Centre Against Apartheid, Prime Minister Vorster discusses South Africa’s policy change that recognizes racial groups in South Africa as a “nations.” This allows South Africa to claim that they allow integrated competition in open international competitions; however, they could not compete as an integrated team. He comments on the fact despite this policy change to appear less segregated, the policy of multi-nationalism provided little to no change on the inequalities in sports for non-whites.

The Sports Boycott

As the anti-apartheid movement increasingly gained momentum in the late 1950s, the international community sought to condeM.N. the racially restrictive laws of apartheid. In response to the influence of apartheid policies in sports in South Africa, many countries began to boycott South African sports in attempts to fight against racial segregation and pressure the South African government to reform their oppressive policies. The sports boycott also involved the banning of South Africa from numerous international events, such as the Olympic Games.

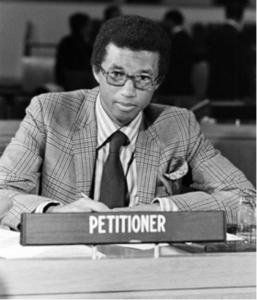

As President of the South African Non-Racial Olympic Committee (SAN-ROC), Dennis Brutus protests against not only the 1977 Davis Cup, but the support of all sports events that allow South Africa to participate. He argues for a sports boycott in order to protest against South Africa’s racist policies.

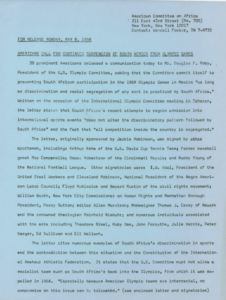

This press release from ACOA details the contents of a letter written by 30 prominent American athletes, civil rights leaders, union leaders, etc. to the President of the U.S. Olympic Committee. In this letter, they urge the President to prevent South Africa’s participation in the 1968 Olympic Games due to their discriminatory, segregationalist practices. This letter is just one example of the efforts made during the sports boycott against South African sports.

The Davis Cup 1977

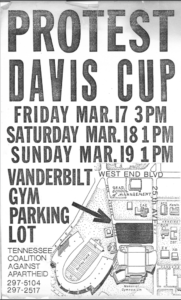

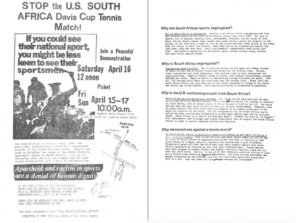

https://projects.kora.matrix.msu.edu/files/210-808-7292/protestdaviscupleaflet.pdf

Tennessee Coalition Against Apartheid leaflet advertising the protest of South Africa participating in the Davis Cup.

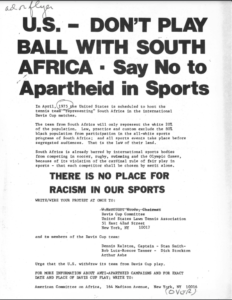

https://projects.kora.matrix.msu.edu/files/210-808-7311/acoadontplay.pdf

In this leaflet, ACOA urges the U.S. to withdraw from the Davis Cup because South Africa’s sports policy does not align with fair play practices.

The Organization of African Unity fight against the Davis Cup, in which the US would play with South Africa; thus supporting Apartheid and racism in sports.

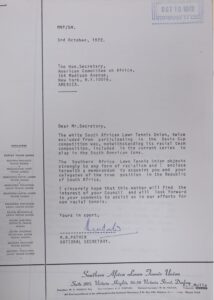

M.N. Pather writes on behalf of the South African Lawn Tennis Union (SALTU) to ACOA asking them for assistance the union’s goals of against racism and Apartheid. He expresses his concern about the fact that the white South Africa Lawn Tennis union was excluded from the Davis Cup due to their segregated team, but were still being allowed to play in South American competitions.

As one of the most prominent African American tennis players at the time, Ashe’s support of the anti-apartheid movement in the realm of sports was highly influential. However, he opposed the sports boycott because he held the belief that isolating South Africa from the rest of the world would prolong Apartheid segregation laws.

As general secretary of SACOS and SALTU, two anti-Apartheid organizations in South Africa, Pather played a large role in the success of the sports boycott. Through his work with the anti-apartheid movement, he never failed to uphold his belief that there is “no normal sport in an abnormal society”; meaning desegregation in sports cannot be achieved until all anti-apartheid legislation is removed. 1

American Committee On Africa

ACOA plays a huge role in promoting the international sports boycott of South African sports. The association took many actions and published numerous pamphlets and press releases advocating for importance of participation in the boycott in addition to supporting the anti-apartheid movement in various other sectors.

A Letter to Arthur Ashe: From M.N. Pather

In 1973, M.N. Pather wrote a letter to Arthur Ashe, requesting him to decline the offer to play in the South African Open Championships. He informs Ashe that interracial tennis does not exist in South Africa despite the government’s new law of multinationalism.

Despite Pather’s letter and request that he decline the invitation to the South African Open Championships, Ashe still accepts the invitation to play in the tournament. In response to Pather’s letter, Ashe writes a letter in return, explaining why he decided to participate in the championship. He stated, “I, more than ever, think that the further contact with the politically active American blacks is essential to speed up South Africa’s transition to normalcy.”

In response to Ashe’s letter, Pather expressed that he regarded Ashe as naïve to the magnitude of racial division in South Africa, which furthered his belief that the façade of the multinational sports policy prohibited movement towards nonracial sports and solidified his overall commitment to his work.

Significance of the Sports Boycott

The sports boycott of South African sports was significant because of the importance and centrality of sports to the white South Africans. “Their exclusion from the international arean was more widely felt than the other academic, cultural, and economic sanctions.” Thus, the sports boycott played a large role in the greater anti-apartheid movement. Additionally, the activism connected to the sports boycott also provided greater awareness about apartheid laws and provided much needed support and power to anti-apartheid groups at the time.

Bibliography

Arsenault, Raymond. Arthur Ashe: A Life. United Kingdom: Simon & Schuster, 2019.

Barnes, Catherine. “Incentives, Sanctions and Conditionality,” International isolation and pressure for change in South Africa | Conciliation Resources, February 1, 2008, https://www.c-r.org/accord/incentives-sanctions-and-conditionality/international-isolation-and-pressure-change-south.

Bersell, Matt. “Sports, Race, and Politics: The Olympic Boycott of Apartheid Sport.” Western Illinois Historical Review, 2017. http://www.wiu.edu/cas/history/wihr/pdfs/wihr-sports-race-politics-olympic%20boycott.pdf.

Chen, Teddy. Arthur Ashe Addressing the Special Committee on the Policies of Apartheid of the Government of the Republic of South Africa. Photograph. New York, April 14, 1970. https://africanactivist.msu.edu/image.php?objectid=210-809-847.

Childress, Contributor: Boyd. “Arthur Ashe (1943–1993).” Encyclopedia Virginia, July 10, 1943. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/ashe-arthur-1943-1993/.

Davis Cup – Protest against South African Participation. Photograph. Nashville, Tennessee, March 17, 1978. https://africanactivist.msu.edu/image.php?objectid=210-809-77.

George Houser Receives Gift at ACOA 25th Anniversary. Photograph. New York, November 12, 1978. https://africanactivist.msu.edu/image.php?objectid=210-809-1877.

Govender, Subry. “Activist Gave South Africa a Level Playing Field.” PressReader.com – Digital Newspaper & Magazine subscriptions, August 20, 2020. https://www.pressreader.com/south-africa/the-mercury-south-africa/20200820/page/6/textview

Govender, Subry. “‘Don’t Play Here, Ashe Urged.” The Daily News. November 9, 1973.

M.N. Pather. n.d. Photograph. https://photos.geni.com/p8/8748/7633/534448377d722e0d/M.N._PATHER_medium.jpg.