Zachary Jordan

May 4, 2022

Mboya was born in 1930, and spent much of his early years living on a sisal plantation with his parents, where his father earned around £2.13 per month. Though it wasn’t much, it was enough to pay for his education, as he attended several different mission schools throughout Kenya as a young boy. He was Suba, a multi-ethnic group within Kenya drawn from various tribes, but he most closely associated with his Luo ethnic roots, with his parents both born on Rusinga Island. 1

He would attend various mission schools throughout his childhood, moving between Kamba and Luo lands as he went. Though he never particularly excelled in school, his grades were good enough for him to continue his education in Nairobi, where he began studying as a teacher but quickly took on training as a sanitation inspector, a position that would afford him many opportunities.

While working in Nairobi, Mboya began to witness inequality and experience racism to a much greater degree than ever before, being paid 1/5 the salary of White colleagues and given a completely different set of requirements. It was at this time that he became involved with the Kenya African Union and started looking up to freedom fighters like Jomo Kenyatta. Though the Labour Department was consistently strict with labor unions, in 1953 they granted official recognition to the Kenya Local Government Workers Union, an organization in which Mboya held a high position.

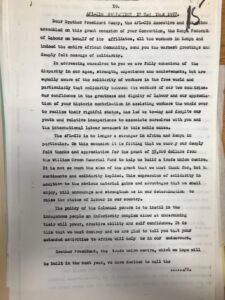

As Mboya’s political power in Kenya grew, so too did his relations with Western governments. In the mid 1950s, he traveled to the U.S., with one of his primary goals being “[raising] special funds […] to support projects in Africa to establish inter-racial co-operation.” He was a guest speaker for the American Committee on Africa (ACOA) in New York, and met with key figures of the AFL-CIO like Maida Springer Kemp, George Meany, and A. Philip Randolph in order to secure these funds for the Kenya Federation of Labour (KFL).

Image: Tom Mboya letter to George Meany (AFL-CIO president)

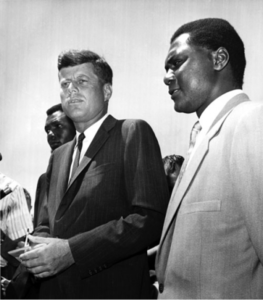

Continuing into the late 1950s and early 1960s, Mboya’s involvement with the U.S. deepened. In the American public eye, his statesmanship was commended: he met with prominent U.S. figures like Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and John F. Kennedy to bolster U.S.-Kenya relations and offer support to the Civil Rights Movement, and his airlift project gave Kenyan students opportunities to pursue university education in the U.S. Through private meetings and public speeches, he was given heroic treatment among many American audiences.

Tom Mboya on Meet the Press, April 1959 https://youtu.be/xeLHxFT6ojs

Image: John F. Kennedy and Tom Mboya

Less well-known at the time, however, were his close links to the CIA, for whom he was a key asset within Kenya. As a powerful figure (the general secretary of the KFL after 1953), a nationalist hero, and a supporter of foreign investment and land ownership in Kenya, Mboya was seen by the CIA as both strategically useful and significantly “safer” than Jomo Kenyatta, the main hero of Kenyan nationalism at the time. Many of his travels were funded by the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU), an organization aimed, in part, at countering left-wing trade unionism, a group for which Mboya later became a regional representative. Direct monetary support was also given to the KFL, as it was seen as a model “free trade union”: advocating workers’ rights without threatening free trade and international investment.

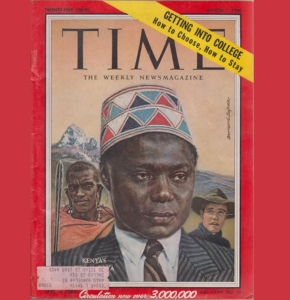

Mboya’s perception within Kenya was much more complicated than his generally positive reception within the U.S. As mentioned above, many Kenyans saw him as somewhat of a hero, as the KFL, in which Mboya was the general secretary, was a key leader in the independence movement following the banning of all other African political organizations in the midst of the Mau Mau uprising. His student airlift project, as well, was quite popular within Kenya.

Image: Students from one of the “airlifts” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Kennedy_Airlift)

In political circles, however, he was a much more controversial figure. His vying for power, as well as his favorable attitude towards the U.S., fostered bitter rivalries. One of his more staunch critics was Oginga Odinga. Despite their close associations and alliances during the 1950s, throughout the 1960s the two competed for President Jomo Kenyatta’s favor and argued frequently and publicly over the course of the newly independent Kenya’s future. Odinga favored closer alignment with the Soviet Union, while Mboya favored relations with Western nations and business interests.

Oginga Odinga

An example of the contrast between his perception abroad and within Kenya; this is, of course, a simplification, as he did have supporters at home and detractors abroad.

Bibliography

David Goldsworthy, “Sisal and Schooling,” in Tom Mboya, the Man Kenya Wanted to Forget (Nairobi: Heinemann, 1982), pp. 4-9.

The CIA’s Global Strategy: Intelligence and Foreign Policy. (Cambridge, MA: Africa Research Group, 1971).