Samuel Panoff

Spring 2022

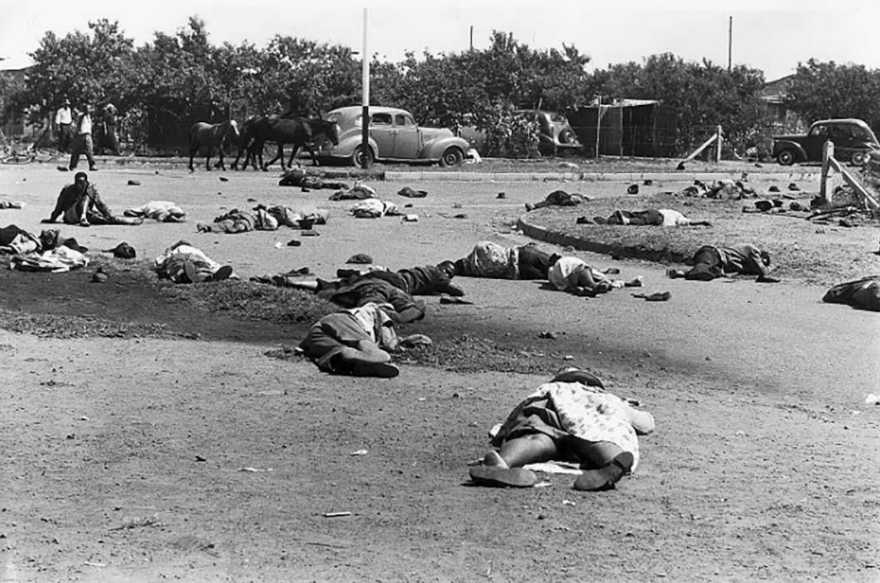

One of the deadliest events throughout apartheid South African history, the Sharpeville Massacre left 69 dead during a peaceful protest.

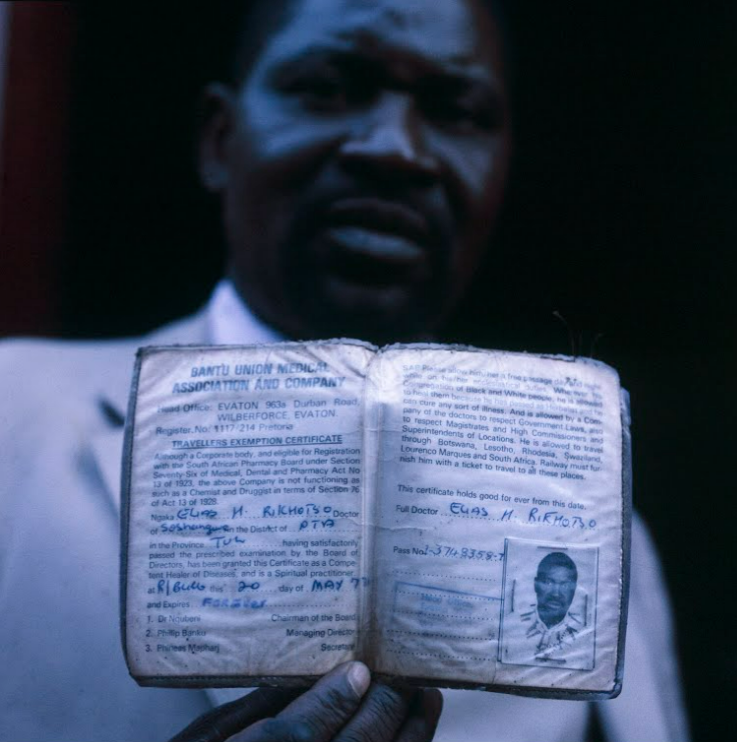

Pass Laws

The Pass Laws Act was established in 1952 and was used to keep control of the African population in South Africa. This law required all African residents to carry around a “reference book” that contained information about the carrier. Police would use these books as an excuse to fine and arrest African citizens who did not qualify for them.

Idea of Peaceful Protest

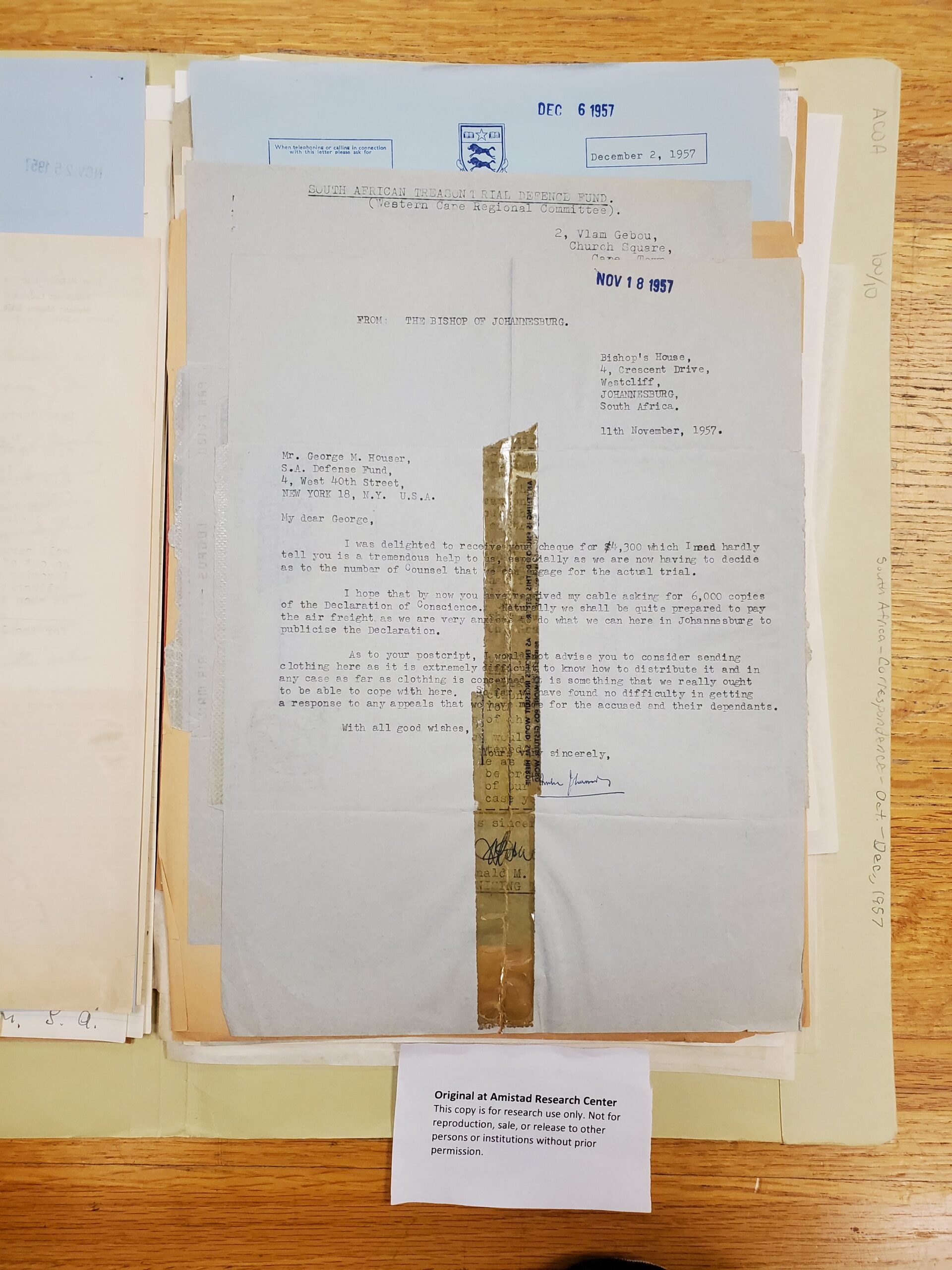

African citizens used a variety of means to oppose apartheid laws. Organizations such as the PAC and ANC staged peaceful protests and boycotts. They would teach citizens the idea of fighting in a nonviolent way. These tactics were used for years pertaining to many unjust laws in South Africa.2 Ambrose Reeves used the Declaration of Conscience to teach his African neighbors the ideas of the right to criticize and protest.3

The Protest

In March 1960, the PAC organized a peaceful protest in the black township of Sharpeville, where people would come to object and burn their reference books. The tone of the protest was cheerful, as protestors carried signs and thousands chanted for the pass laws to be abolished. It took a turn for the worse when police showed up.4

The Shooting

Throughout the protest, swarms of police and armored vehicles began to occupy the area. They pointed their guns at the large crowd and started to open fire. Many of the protestors were shot in their backs as they were trying to escape the scene. In the end, sixty-nine African protestors were killed, and hundreds were injured.5 Lydia Mahabuke, one of the protestors, felt a shot in her back while trying to escape. “After having felt this, I tried to look back. People were falling, scattered. There was blood streaming down my leg. I tried to hobble. I struggled to get home.”6

Domestic Response

There were mass funerals for the victims, yet within the township of Sharpeville, there was no response to the event, as people who spoke against the government were detained by the police. There were a variety of responses from different leaders and organizations in South Africa. Figures such as Nelson Mandela and Chief Albert Luthuli burned their passbooks in protest. There were also countless protests, including a large-scale one with tens of thousands of people in Cape Town. The government would eventually call for a state of emergency and ban any sort of gathering.7

Ambrose Reeves also tried to help by rushing to hospitals around Sharpeville to interview some of the injured protectors. He hoped that these accounts would help bring national attention to this tragic event.8 Reeves would end up being arrested and exiled from South Africa due to his vocal protest of the South African government.

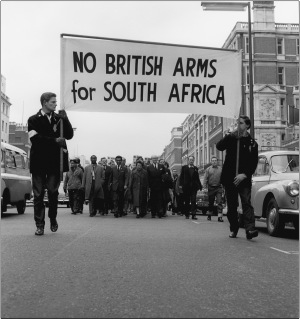

International Response

There was an array of international response by various countries. The United Nation called for the abolition of apartheid and condemned the massacre on April first. Within the coming months, the UN declared that apartheid was a violation of their charter and placed economic sanctions on South Africa. Though their government became isolated after this event, it did not stop them from continuing to administer apartheid law.9

Conclusion

Though the Sharpeville Massacre brought the horrors of apartheid to the eye of the international world, it didnot stop the South African government. In the months following the massacre, thousands of Africans would bearrested for protesting the government, and groups such as the ANC and PAC were banned. It would take yearsofboth violent and nonviolent protest, along with international pressure for apartheid to finally come to an endthirty years later. The Sharpeville Massacre is an atrocious part of South African history, but it is important toremember about this and othersimilar moments to make sure it never happens again.

Bibliography

2. Matthew Mcrae, “The Sharpeville Massacre,” CMHR, n.d.

3. Ambrose Reeves, letter to George M. Houser, 11th November, 1957

4. Matthew Mcrae, “The Sharpeville Massacre,” CMHR, n.d.

5. Matthew Mcrae, “The Sharpeville Massacre,” CMHR, n.d.

6. Matthew Mcrae, “The Sharpeville Massacre,” CMHR, n.d.

7. “Aftermath: Sharpeville Massacre 1960 – Sahistory.org.za,” South African History Online, June 13, 2011.

8. Ambrose Reeves, “The Sharpeville Massacre – a Watershed in South Africa,” n.d.

9. “Aftermath: Sharpeville Massacre 1960 – Sahistory.org.za,” South African History Online, June 13, 2011.